The Financial Administration in the wake of Makó and Imrecze: countless unnecessary audits, a language quiz instead of tax expertise

We analyzed the extent to which corruption is related to Slovakia’s tax evasion problem

The arrests of several ex-tax officials confirmed what the media had been suggesting for a long time. Officials at the Financial Administration (FA) abused their power and millions of euros were repeatedly misspent on overpriced IT systems. Those were, despite the price, often less than helpful in combating tax evasion.

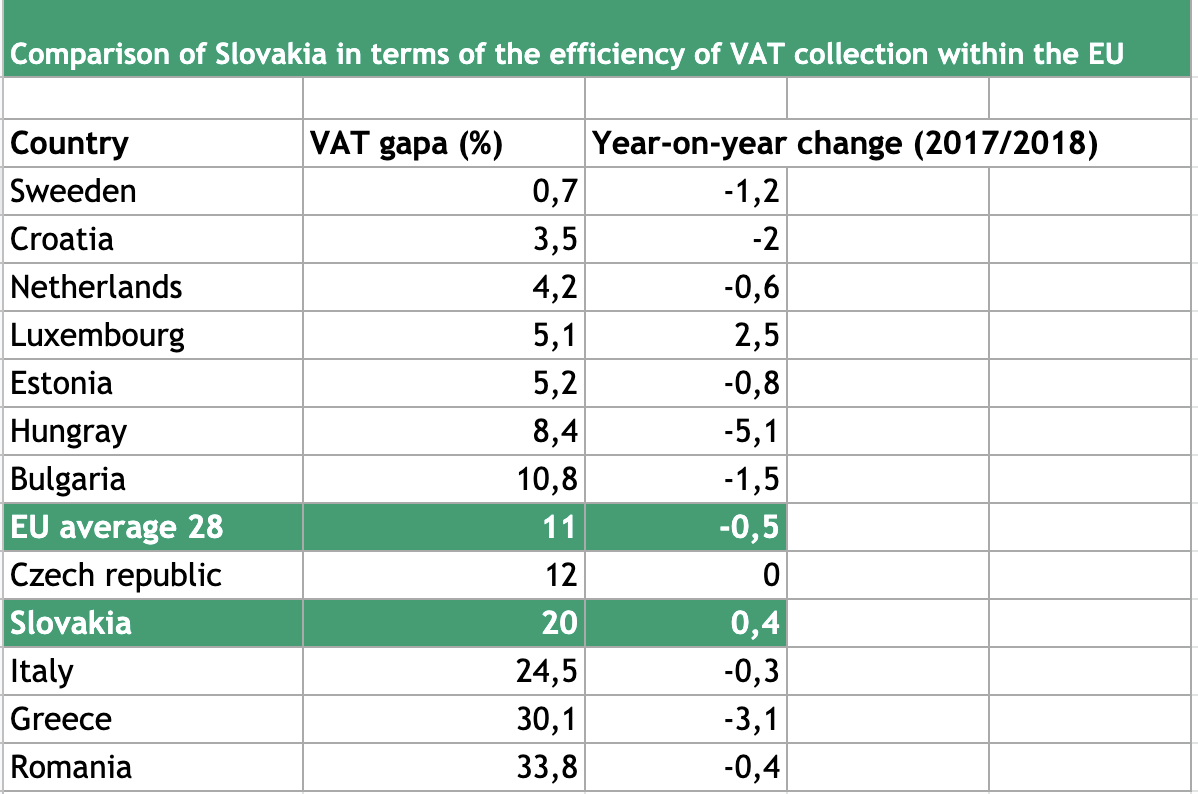

This sheds a whole new light on the puzzle we have been trying to solve: How is it possible that, despite many strong tools, Slovakia is still lagging behind in terms of VAT collection in the European Union? Annually, we lose more than one billion euros on this tax alone. And according to the latest estimates from the Institute for Financial Policy, which operates under the Ministry of Finance, we are likely to lose hundreds of millions more in business taxes.

Meanwhile, in the face of a slowed economy due to the pandemic and the planned tax reform from the works of the new Minister of Finance, Igor Matovič, the state treasury is going to need each euro.

Therefore, in the newest analysis we took a closer look at the Financial Administration, its functioning and its fight against tax and customs duties evasion. The analysis is primarily concerned with the period of the FA under the previous management, which has been gradually replaced since last year’s parliamentary elections.

In the analysis, the author processed information from meetings with experts with ties to the FA as well as its employees. Also included are the conclusions of the Institute for Financial Policy and assessments of TADAT, which is an organization working with various world institutions with the goal of analyzing shortcomings in tax systems.

Good tools in the wrong hands

When asked what the FA’s greatest hurdle in combating tax evasion was, the most frequent answer from different people was: “personnel policy”. Other problems then mounted, such as insufficient analytics when selecting companies for audit, weak assessment of the results and keeping up with trends in fraud. But there is also talk of non-transparent allocation of employee bonuses and concentration of information in the hands of a few individuals.

If we look at the tools the FA uses to collect taxes, the assessment of the organization TADAT (Tax Administration Diagnostic Assessment Tool) will help us here. TADAT is partnered with European countries, but also the World Bank and many other institutions. TADAT recently published its assessment of the Financial Administration of the Slovak Republic

It praised the strong focus on VAT audits, the entrepreneurs’ discipline in paying their taxes and the widespread use of electronic cash registers instead of cash payments, which are more difficult to inspect. All of that facilitates good tax collection.

But TADAT also pointed to several problems. For instance, the insufficient auditing of business taxes. Tax officials’ reckless spending on new measures as well as „a large reserve of old tax debts“.

Experts also call on the FA to communicate much more actively with taxpayers and explain the collection of taxes more clearly. Public opinion polls could be one way to do it. This is important because up to half of the uncollected business taxes may not be due to fraud, but rather due to ignorance of the rules, according to the estimates. Taxpayers are also liable to misinterpret them, especially small businesses, and entrepreneurs.

1. Analytical brain in Banská Bystrica

The main tool of the FA are tax audits. To help aim them at fraudsters and suspicious businesses, the VAT control statement (VAT CS) was established in 2014.

It is a form which companies registered for VAT regularly send to the FA online. In addition to the tax itself, it also contains a list of invoices, so tax officers can put together a more accurate picture of the company’s business in a month or year-quarter.

At the same time, VAT CS helps to match transactions with suppliers via invoices and verify whether they also entered the same invoices in the accounts. Simply put, VAT CS reveals fictitious invoices through which entrepreneurs tried to reduce their taxes.

The data from the VAT CS are compiled in the center for analysis in Banská Bystrica. It operates in secrecy, for the most part, and is thus somewhat akin to Columbo’s wife. There is a lot of talk about it but hardly anyone has actually seen it.

However, interviews with people from the FA reveal the center does not exactly enjoy the best reputation. „Poor“ output was the most common complaint.

One of the respondents, with whom the Foundation talked about the FA, stated on the topic of the center: „Given how much information they have in (Banská) Bystrica — and they have everything there — even if I asked for some information, the output was null.“

Hence, we should probably dismiss the detailed networks of companies presented as the output of VAT CS at press conferences.

To illustrate, annually the auditors send about 5,000 requests to the center for analysis for roughly 7,000 entrepreneurs. That means generating an average of less than twenty business contacts from the IT system on a daily basis.

The new president of the Financial Administration, Jiří Žežulka, does not expect the center for analysis to ever be perceived positively by the auditors. „Audits are increasingly being issued centrally, in part as a result of the center’s output. Thus, they might see it as adding work.“

However, the respondents noted the center does not automatically pass on its findings from the VAT CS to auditors and investigators, but rather waits to see if anyone comes asking about the dubious taxpayers.

The Foundation also met with complaints that the data from the center was being misused to order. For example, to eliminate an inconvenient competitor via targeted audits. Though, it should be noted that no such case has officially surfaced in public so far. The management of the center has not changed even after last year’s replacement of the FA’s president.

There is one more official overseeing the analysis data

The center and its head fall under the Director General of the Anti-Fraud and Risk Analysis Section.

There was a replacement last year. Rastislav Gábik took charge of the section after Ladislav Hanniker. Mr. Gábik defended his elite analysis department.

„We cannot give out complete information from VAT CS, because they are handled in secrecy, but also due to leaks from the FA,“ he added.

Leaks of tax information were a topic in itself. From waving protocols from tax audits on politicians‘ press conferences to anonymously distributing tax officers’ findings to opposition politicians online. However, it is true that we have yet to encounter any data leaks from the VAT CS, i.e., chains of commercially connected companies.

Furthermore, Gábik denied the center not actively passing suspicious companies forward. „The center recommends audits in hundreds of cases each month.” Another question is: What has the management been doing about it until now? After all, they have the final word in what gets audited.

List of suspicious businesses and entrepreneurs is sent to the head of the anti-fraud section as well as tax criminalists, who have their own superior. Next it is decided where the audits will be sent.

The VAT control statements should not however be seen as a cure-all. As a tool that reveals all tax evasion and fraud. They can reveal unpaired transactions, i.e., when one company reduces its tax revenue via invoice X, but another does not state the same invoice X and does not tax it. They can also be used to reveal carousel fraud.

However, control statements are of no use in the grey economy (without receipts), which is still widespread in gastronomy and accommodation services. With no receipt, there is nothing to inspect. The tax IT system is simply unaware of the transaction.

At the same time, the director general of the section also determines the strategy of the center for analysis. „There was no need to focus exclusively on VAT CS and recorded transactions,“ Gábik assessed and added that because of the focus on VAT, there are not enough resources in other areas, such as business tax auditing.

Aside from VAT, audits are lagging behind

The focus on VAT audits was criticized not only by TADAT but also by analysts from the Institute for Financial Policy. For instance, last year they ran into trouble while trying to estimate business tax evasion because the number of audits they could analyze was limited.

Databases full of „dead“ companies are also a big issue. There are roughly 30,000 of them, which is about one sixth of the total number.

According to one IFP analysis, up to 50 percent of audits were conducted on inactive companies. From analysts‘ point of view, it is a waste of resources because attempting to enforce this additionally imposed tax liability is almost completely futile.

The problem is inactive companies get into the FA’s databases via the Commercial Register. „The law states that a company entered in the register shall file a tax return. If it fails to do so, we are obligated to serve a notice. If it does not respond, we send an audit, which is pointless in case of an inactive company, but it nonetheless strains our resources, “ Gábik explained.

The good news is that the Ministry of Justice is working on changes that should cleanse the Commercial Register of inactive companies in time. But these companies are not the only source of unnecessary strain for the auditors. Poorly defined objective of an audit is another example.

„Tax audits can sometimes be inefficient, protracted and auditors may focus on the wrong things,“ said Miriam Galandová, a partner at PRK Partners and Vice President at Slovak Chamber of Tax Advisers.

She also points to the risks for entrepreneurs. If the tax office withholds a VAT refund for several months to a company which conducts business primarily abroad, it could prove ruinous for the entrepreneur.

Yet the means of defense are limited. „The entrepreneur may file an appeal against the protocol, but the protocol is drawn up only after the audit has concluded, which can take months. Then there is the option to go to court, but that is time consuming, “ Galandová continued.

The system, however, in part forces the filling of an appeal. Paradoxically, if the entrepreneur accepts and pays the additionally imposed tax liability, a criminal complaint to the police might follow. A sum of 266 euros was often mentioned in the media.

However, the FA calms the situation: “We act rationally when we file criminal complaints. It is not in the interest of the Financial Administration to criminalize taxpayers simply due to the additionally imposed tax liability exceeding 266 euros. Further criteria must be met to reach the standard for criminal charges. „

In other words, if the case does not seem to involve any unlawful conduct or suspicious signs other than the 266 euros or higher additionally imposed tax liability, the FA is not obligated to involve the police.

Differences between regions

As a positive example of combating tax evasion, a tax expert cites stricter rules for company mergers and strengthening of legal sanctions against previous directors, not just the current one.

Merger of companies was, until recently, a popular method of fraudsters for making auditors’ work more difficult and for „sweeping“ the accounts under the rug.

Another practice, used even today, is to move the business to a region where auditors are more overwhelmed with work. Chances their company gets selected for auditing are thus lower.

It is understandable that the capital and its surroundings is home to the largest number of Slovak companies. Over 260,000, in fact. However, the companies-to-auditors ratio reveals that Bratislava’s tax office is greatly undersized. While an auditor in Bratislava handles an average of 1,101 companies, an auditor from Banská Bystrica or Trenčín handles an average of 650. Almost half as many.

What might help:

The FA needs more central management of audits (the strategy is already in the works). Focusing on more than one tax (We lose about 25% of revenue from business taxes. As for income tax, curbing the „cash-in-hand“ method of paying wages or bonuses could work). Better analytical work with already available data. For instance, comparing taxpayer’s income against assets. A positive example is the introduction of serving notices to real estate sellers to pay the sales tax.

Supporting taxpayers with information and encouraging them to pay taxes willingly – finding out what confuses them, reminding them of deadlines. It is necessary to work with the police and to clarify the conditions under which levying of additionally imposed tax liability via the so-called aids is acceptable. The FA does that, but there is no accounting. The tax is simply being based on the last available data. The police though often reject taxes calculated in this manner on the grounds that they are relatively inaccurate.

The Ministry of Justice is already preparing changes to „cleanse“ the Commercial Register of inactive companies. The owners have not officially dissolved them for various reasons, and they still have an entry in the Commercial Register. The FA thus still interacts with them.

Restricting virtual registered offices. There are cases when a single small apartment serves as a registered office for a dozen companies.

Reinforcing auditing capacities in regions with a high number of registered companies. This is also possible via reassigning auditors from other regions, as their jurisdiction is statewide, not limited to any one city or region.

Working out cooperation with the finance division of NAKA (National Crime Agency). Overall, the interactions between the FA and the police seemed more like competition than effective cooperation. To a large extent, it was also related to information leaks on both sides. Therefore, the planned joint flow of information, from the center for analysis for example, is a pipe dream rather than a realistic goal for now.

For the planned “eFaktúra” project (e-Invoice), reconsidering the necessity of the strict secrecy measures as with VAT CS.

Simplifying the criminal procedure. For example, testimonies must be repeated multiple times throughout the investigation, which prolongs the case considerably. As a result, the state is in a bad position to recover any lost revenue. An example here would be the transfer of Ladislav Bašternák’s business and assets to his family before his conviction.

2. Billion euro debts

Old tax debts are a problem the FA has been struggling with for a long time. They often arise when fraudsters repeatedly merge their companies that are in debt with other companies in similar state. The result are businesses with tax debts as high as tens of millions of euros, with directors abroad and offices at hard-to-find addresses.

For illustration, at the end of January this year, the FA registered almost 330 entities that owed at least one million euros in taxes. Added together, it came up to almost a billion. That is a decent sum of money that could be taken advantage of.

How has the FA been dealing with these debts? With a hands-off approach, so far.

„Older debts eventually get transferred to the state-controlled Slovenská konsolidačná (“Slovak Consolidation PLC”). They are removed from the FA’s statistics, which improves them, but the debts do not vanish. They simply get moved to another state institution, “ says analyst Pavol Suďa of Finstat.sk.

This has also happened with several publicized VAT cases. The companies mentioned in media articles kept merging with others until a single company remained, owned by a homeless person or a Hungarian citizen, with a debt of several tens of millions of euros. But after a few years, it „disappears“ from the FA’s list.

Slovenská konsolidačná is a state-owned public limited liability company that has been enforcing debts for state institutions for a long time. Apart from the FA, it enforces debts for other offices as well, from private persons and companies.

The FA transfers debts to konsolidačná if they are older than five years or the debtor is in liquidation or bankruptcy.

However, newer debts remain in the hands of the FA, where there is a chance to recover some of the lost revenue. It is possible to initiate a tax distraint within 20 years of the debt’s incurrence. FA’s statistics show thousands of distraints being initiated annually. Last year, over a 100 million euros was enforced via distraints despite the deferral of tax liabilities due to Covid. That is a decent sum, but still low compared to the overall debt.

Why then do the tax officers not act sooner before debts reach such dizzying heights? They do, but perhaps with insufficient force.

In line with the procedure, they first serve notices to the debtors. Last year, there were more than 100,000 notices served. The feedback is not exactly encouraging though. Taxpayers paid approximately 50 million euros (7 percent) from a total of 700 million, after receiving notice. The year before, it was 44 million from a total of 600 million, or 9 percent.

The new head of the FA Žežulka explained they definitely plan to improve in the area of enforcement. Steps have already been taken to improve technical equipment of that particular department. Faster exchange of information between the FA is crucial here, so that assets can be frozen as soon as possible.

There are also new options such as withholding a debtor’s driver’s license, thanks to the new statute passed last year.

However, he is skeptical about existing older debts. Chances of recovering anything is close to zero, mainly because debtors often lack assets in any form. Alternatively, other debtors make claims on the assets as well and are often faster than the FA and thus compensated first.

What might help

New legislation has enhanced the legal liability of previous directors of companies rather than just current ones. This gives the FA and the police a powerful tool against the greatest tax debtors.

Also, Slovenská konsolidačná is said to start publishing data on transferred tax liabilities to dispel any notions they vanish.

3. Financial Administration Criminal Office

The Financial Administration Criminal Office is a separate branch of the FA, also known by the acronym FACO (KÚFS). In recent years, its activities have been publicized mainly in connection with two events – it was its employees who pointed to Bašternák’s suspicious two million VAT refund back in 2013. And then there was talk of blackmailing entrepreneurs by this office, after the raids in the construction company Dúha, three years later.

Until last year, the office was run by Ľudovít Makó, who is currently being prosecuted. Charges against him are often related to his work at the FACO.

Monitoring, screening and intellectual property – the scope of the FACO

The FACO deserves much more attention, but also oversight. It is a relatively influential office with strong competences. For example, in addition to VAT on import and customs, its competences include monitoring, wiretapping as well as searching for suspects in tax and customs offences. If it is “necessary for the state’s security,“ the office can even take actions normally relegated to tax or customs officers. Additionally, it can screen people using databases containing sensitive personal data, but it also covers the area of intellectual property.

The FACO is relatively independent within the administration. The head of the office is appointed by the president of the FA. The president also determines its organization. The head then directs its activities via internal regulations.

In terms of salaries, it is one of the higher rated offices. Last year, the average gross salary reached 1,850 euros. For comparison, a tax auditor earned on average two hundred less per month.

As it turns out, the case of Dúha was not an isolated instance of this elite organization’s breach of procedure. The Foundation knows of at least two more cases, when during a raid, members of the FACO wrapped company’s accounts in black plastic bags and were refusing to give them to the entrepreneurs for several months. As a result, they were unable to file a tax return in time.

Finally, one year after the raid the accounts were returned and the entrepreneurs discovered the sealed bags were untouched the whole time. The FACO did not even file a criminal complaint for tax evasion. The companies brought their grievances to the management of the FA, but without success.

On the other hand, the FACO’s official statistics seem to be good. Last year, the office processed more than 1,500 criminal complaints with an estimated loss of 200 million euros in revenue. This is due to the fact that during Makó’s tenure an internal regulation mandated all criminal complaints within the FA must first go through the FACO.

A criminal complaints section was also set up and headed, until last year, by FACO’s deputy who was also Makó’s neighbor and former colleague.

FACO ordered 40 seizures of property last year. All of them involved bank accounts

The way FACO uses one of its final tools for combating fraudsters is not ideal, however. Recently, tax officials introduced the option to freeze assets while investigation is in progress. That is key since fraudsters are quick to get rid of money and businesses.

The office can not only freeze money in banks, but also cars and real estate. Alas, they never do. All the 40 interim measures were aimed at bank accounts only.

What might help:

Fully utilizing interim measures and targeting all assets, including cars and real estate. This is crucial in various VAT carousel frauds, where dozens of companies are involved in repeated resale of the same goods. Fraudsters use banking apps that notify them about incoming payments. The money stays in the account only for a few minutes before it is moved. Seizing bank accounts thus rarely yields any money for the state. Conversely, freezing the suspects’ assets such as cars, buildings or land can lead to greater recovery of money, if the suspects are found guilty.

4. Selection procedures

The most frequently mentioned problem of the FA is personnel policy. It does not concern just the highest positions. Those, for the most part, change with the change of state’s government. The issue lies in the method of selecting people for the FA.

Selection procedures are announced on the FA’s website as per the needs of individual offices. Their number reaches three digits each year. Looking at the description of the required skills, one might sometimes get the feeling the administration is not actually looking for tax or customs experts.

The statutory course for these procedures is partly to blame here. It is too formal. Expecting technical questions from the field might lead to disappointment.

Instead, the core of the written part is a multiple-choice Slovak language test. The same test is required for common auditors and high officials alike. Applicants might be asked to choose the correct prepositions, for example.

This is supposedly followed by a written quiz to test their expert knowledge, according to the FA. In practice, however, an oral interview is often all that takes place.

And yet, working for the FA is very attractive in terms of salary. On average, gross salary exceeds 1,700 euros, the auditors earn roughly a hundred less. Criminal office employees are in the upper tier.

The Foundation was approached by multiple applicants who questioned the expertise of the winning candidates. They also point out unsuccessful candidates are told the results without any justification as to why they did not win. Thus, it is not possible to appeal.

The Financial Administration argues it follows the statutory procedure. Among the nine requirements, the law does indeed mention medical and legal capacity as well as knowledge of the state language. A candidate must also not be a member of a political party.

There is only one professional requirement – achieving the appropriate level and type of education.

And so, the Foundation came across a bizarre case of a long-term customs officer vying for promotion and losing to a candidate with no previous experience in the field.

The failed candidate took it to court, where the FA argued the winning candidate studied at the Faculty of European Studies while the plaintiff had teacher education in natural sciences. According to the FA, the winner’s educational background was “objectively” more suitable for the position.

The district court finally dismissed the action. The prosecutor’s office responded similarly to the request to investigate the superior’s conduct.

In another case, a tax auditor had been working for years in the civil service, not as a permanent employee but rather a substitute, for example for workers on maternity leaves. “I took part in a selection process as a working auditor and lost to someone who had nothing to do with tax auditing,” she described her experience.

The suspicions that family affiliation is more important during the selection process than expertise, are also affirmed by many publicized cases.

Makó was not the only high-ranking official to be arrested

Ľudovít Makó is probably the most notorious tax official these days. He has been in charge of a group of elite tax criminalists since 2014, until last year. Since last year, he has also been prosecuted for several serious crimes, but thanks to his testimonies, Slovakia also learned about a well-organized and coordinated criminal group. This group, a so-called “octopus”, had its tentacles wrapped around the Financial Administration, the police as well as the Slovak Information Service and operated through them. Makó secured access to administration’s intelligence via internal regulations and thus had first-rate information. All criminal complaints related to taxes or customs, flowing from the administration to the police, had to go through him or people close to him. Any requests for tax or customs officers by the police had to go through his office first as well. As a result, Makó was exceptionally well informed on tax evasion suspicions and knew which persons were of interest to the police and investigation bodies.

Long-term President of the Financial Administration František Imrecze, who headed the administration from mid-2012 until autumn of 2018, is currently being prosecuted in custody for suspicions of public procurement fraud in the IT area. A president gets appointed by the Minister of Finance.

Even older nominations did not fare much better. For example, the previous vice president Dušan Pátek, had active correspondence with the now convicted Marian Kočner via Threema. They regularly discussed matters relating to Pátek’s position.

Even directors nominated by previous governments, such as Miroslav Mikulčík, were associated more with scandals than career successes. Mikulčík specifically was withdrawn from his position in the spring of 2011 by the then Minister of Finance Ivan Mikloš (Christian democrats, SDKÚ). But there is more. A case was revealed where an SDKÚ’s functionary was found to have profited from the renting of a building to the Tax Office of Košice. Mikulčík later returned to install a new IT system for the tax office. This led to a system failure at the turn of 2011-2012, which not only had an impact on the parliamentary elections results but also significantly impaired VAT collection.

- Idle inspection

Abuse of power or failure to perform duties are the responsibility of the FA’s inspection section. The Foundation spoke with several respondents, who had many criticisms of its functioning under the previous management. The statistics up until the previous year are not reassuring either.

For example, last year the inspection examined 167 complaints against the FA’s employees. It managed to fully process only 60, which is not even half. The employees themselves seemingly did not have much trust in their own control body, given the number of complaints coming from among their own ranks. Last year, they passed only eight complaints to the inspection.

On the other hand, last year there were five cases where the FA „bade farewell“ to employees for misconduct. The year before, it was four. As for failure at work, only a single tax auditor was dismissed throughout both years.

The authority of the inspection differs depending on whether a case involves abuse of power or misconduct. In the former case, tax inspectors must pass any findings on to the interior ministry’s Bureau of the Inspection Service, in compliance with the new act on the Financial Administration. The bureau also deals with cases such as police misconduct. In the latter case however, if the tax inspection finds, say, alcohol consumption at work, it can initiate disciplinary proceedings on its own.

People familiar with the inspection’s situation primarily criticize its staff. The Foundation knows of several cases of people being hired not because of their professional profile, but because they needed to be “tucked away” somewhere. Their previous post may have been eliminated, for instance.

Another problem is the retention of information, which can last up to several months and essentially amounts to a failure to act in the reported cases.

However, for the sake of objectivity it should be noted the task of the inspection is not easy in terms of the form of employment. People in the FA work in civil service employment. Potential lay-off could prove to be a great liability for the employer, which in turn provides a strong protection for the employees.

Simply put, if you dismissed someone and the suspicions of a breach of duty failed to be confirmed (e.g., by a court verdict), you would run a risk of having to pay compensation to the employee in question. For that reason a form of agreement with an „inconvenient“ employee is often chosen instead, or reassignment to a lower position.

The inspection has had a new director for several months now and promises to „change the culture and cleanse the FA“. The numbers should supposedly confirm this as well. In the first half of the year, the inspection initiated more disciplinary proceedings (35) than in the whole of last year (23). The number of criminal complaints filed against the FA’s employees is also growing.

In the spring, 10 inspections were conducted at the border crossing with Ukraine. The result is eight initiated disciplinary proceedings.

What might help:

Defining precisely what the tax auditors need to inspect and do so that entrepreneurs’ tax deductions can be approved. The case of Bašternák’s VAT return demonstrated that what was deemed a regular purchase of luxury apartments by the tax auditors (and the inspection agreed years later) was considered a tax fraud by the employees of the FACO, while looking at the same documents. The problem is that the auditors did not formally violate anything. A purchase contract often suffices and entrepreneurs verify the rest of the information verbally. However, another auditor might in a similar situation request additional documents, such as an invoice, which reveals the transaction either never happened or could not happen as described by the entrepreneur. However, both auditors acted correctly and in full compliance with the formal procedure.

The forthcoming amendment to the Financial Administration Act is to strengthen the powers of the inspection: The FA’s investigators will be able to monitor them and tap their conversations straight away as well as demand an explanation.

- What we can learn from the Netherlands

The words Netherlands and taxes together often conjure up ideas about offshoring. These are schemes in which companies use their Dutch offices to avoid taxes. The work of the local tax institutions responsible for tax collection remains overshadowed. However, that is what they excel at, within the Union.

The Netherlands have one of the lowest VAT gaps in Europe, which is a generally accepted measure of tax collection efficiency. This means Dutch tax officers are able to obtain nearly all of the VAT for the state budget, which can, in theory, be calculated on the basis of completed transactions. And the country is successfully reducing this gap even further.

For comparison, Slovakia lost one fifth of the VAT revenue in 2018. The Union average was 11 percent, but the Netherlands lost only about four percent.

It is also partly due to the sophisticated investigation and reporting tools the tax authorities employ. For example, they have an independent investigation service called FIOD, which monitors and fights tax and financial fraud.

The Tax Cobra is the closest Slovak equivalent, but it does not have a legal personality. It was more of a name for meetings of the police and the Financial Administration.

However, the Dutch FIOD has an independent investigation team – Team Criminal Intelligence (TCI), which specializes in uncovering and combating organized crime. For example, money laundering, bankruptcy fraud or VAT carousel fraud.

At the same time, investigators have to deal with new trends such as money transfers via various cryptocurrencies, which are transparent and harder to monitor.

It is interesting to see how the TCI handles working with informants – their identity is never revealed outside the TCI, „not even the judge knows who provided the information“, FIOD representatives explained, because the protection of informants is enshrined in law. Non-profit organizations in the Netherlands also have an interesting position when it comes to monitoring international financial flows. There are several of them dedicated to monitoring tax evasion. They draw attention to the fact that international companies are sometimes able to „secure“ better tax conditions for themselves than local entrepreneurs.

Why is this independent office that investigates big tax evasion cases important? For starters, its scope and contacts in neighboring countries. According to FIOD, up to 80 percent of investigations are in fact international in nature.

FIOD therefore uses various forms of smart data analysis, where its analysts link data from public databases, criminal files, foreign databases and their own investigations. However, the exchange of information on new trends with investigators from other countries is also important.

Finally, the area where differences between Dutch and Slovak institutions are palpable is communication with the public. For example, FIOD has published on its website not only its strategic three-year plan up to 2022, but also current goals and vision for this year.

When asked whether this gives fraudsters an opportunity to operate in less controlled areas, FIOD as well as other experts says no. Because even TADAT criticized the Financial Administration for lack of communication with the public regarding their upcoming measures as well as strategic steps.

Interesting facts

– The competence of the Criminal Office of the Financial Administration also includes the protection of intellectual property rights.

– Armed members of the FA, like police officers, are entitled to retirement pensions. At the end of last year, their average amount was 527 euros.

– Tax cases are burdened by protracted investigations also due to reversed evidentiary procedure. While the taxpayer has to prove his/her innocence to the tax officers, it is the opposite for the police – the police have to prove the entrepreneurs guilt. Therefore, the process of gathering evidence often has to take longer.

– The UNITAS project, which is supposed to unify the collection of taxes and levies and turn the Financial Administration into something of a Slovakia’s great wallet, can be compared to the highway project from Bratislava to Košice. UNITAS has often been mentioned by politicians and their program statements, and this time it is no different. The concept of unified collection of taxes and levies was approved by the government for the first time in mid-2008. So far, only the first part, which merged the collection of taxes and duties, has been completed.

The project was financially supported by the Dutch Embassy as part of a project aimed at strengthening the rule of law and better functioning of public institutions .